I’m immersed in the life and work of Andrzej Jan Wroblewski, a Polish designer who grew up in the Soviet era Eastern bloc, going to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in the 50’s. After the Cold War defrosted a bit, this miraculous person travelled to see France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy in 1958. Within a decade of that, Wroblewski won a Ford Foundation fellowship to spend time studying art in New York. Although he began with sculpture and photography, this artist made his mark in design. He built and strengthened departments of industrial design in both Warsaw and in the US, serving as Dean in both instances.

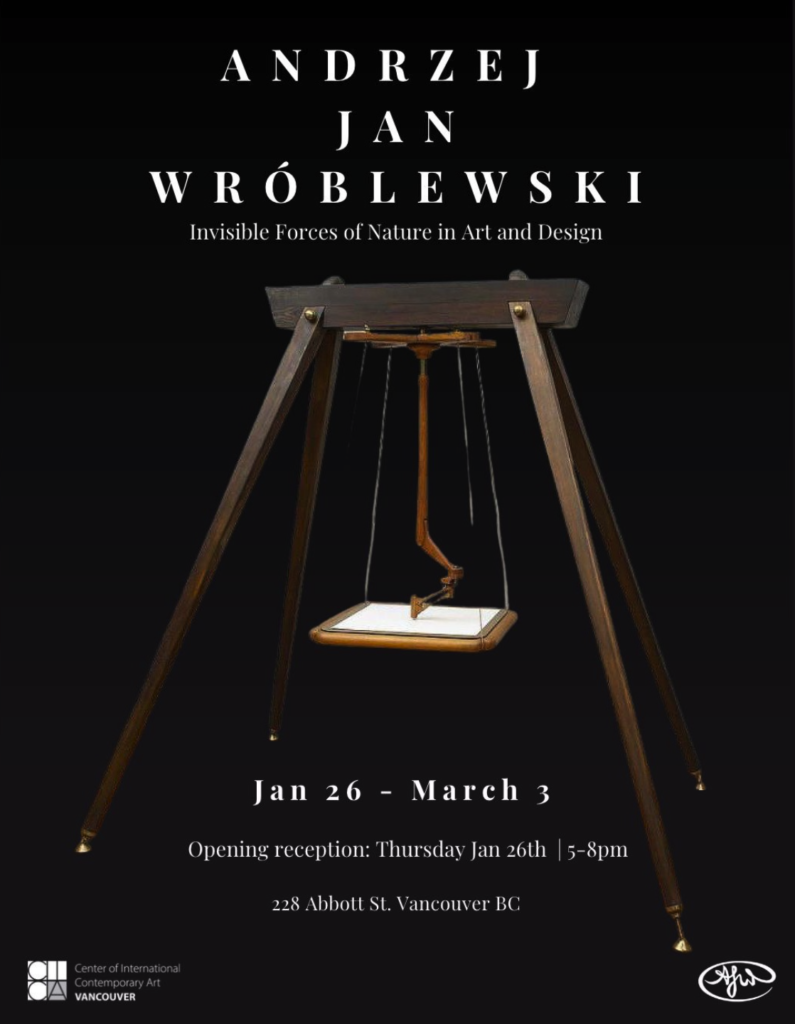

I’m prepared to drive to Vancouver tomorrow to interview Wroblewski concerning his current solo exhibition at the Center for International Contemporary Art. While I knew a little bit about design heading into this project, what fills my head now are philosophical and practical applications of this most practical of art disciplines. How does a designer read the world, how do signs constellate Wroblewski’s world, and how does he create meaning from what he reads in everyday life and society?

Which brings me to our series on The Importance of Walking in Poetry. I started this series back in December of last year, when our first snows were falling. Today it’s snowing again, probably our last, all these big globs of snow prancing down to plop on the earth, blanketing particulars of a nascent spring. Part 1 was on observation, Part 2 on inspiration, and Part 3 on rumination. Today we’re talking about reading, and I want to dwell on reading as a way of living and moving in the world, not just what we do with books.

I shall try and get out for a walk today, as should you. I recommend a good browse, both before and after your walk today, through the Igneus Bookshop. There you’ll find over three decades of collectibles by masters of poetry and existence by authors such as Julia Wendell and S. Stephanie, writers who have done more than their fair share of rumination, digesting the very difficult to digest grasses of life and politics, alchemizing realisations in stanzas and lines of poetry.

The four main ways in which walking helps to read and write poetry are:

Reading

We’ve talked about how taking a longish walk can clear our mind and move us into a mode of pure observation. Then we feel inspired, or filled with spirit (natural, human, and celestial). German philosopher Immanuel Kant spoke of aesthetic observation as that which untethers our rational mind and gives free rein to imagination. It can be more simple than that. As we turn a corner in a forest, we may notice how the light slants differently upon a broken white birch, or how the quickest leaves to un-sheath and grow are those that receive full sunlight for most of the day. We begin to form relationships between things, such as light and spatial position, or between growth and seasons. We begin to build patterns and structures that represent our world to us. Then we internalise these representations, building out our inner-world.

All of nature, indeed the whole world, is a book laid open for us to read. Walking through nature, there is a reset that happens. Built environments of home, workplace, and store are left behind. We experience a purity and simplicity only nature can provide. Some of us, surely, will be walking through cities, or through town centers. The key to this kind of walking is to let go of purpose, will, and obsessive thought. Allow our mind to rest, and new information will present itself in harmony with our inner-world.

There was a group of Parisian social activist artists and thinkers known as the Situationist International (SI), represented to most of us today by Guy Debord. The group was active in the 1950’s and 60’s, and their main thing, their main activism consisted in the act of walking. They took long long long walks, known as dérives, through Paris at night. They’d walk with no plan in mind, the only thing they expended effort on was to try and be sensitive to the city streets, themselves. To hear the streets, feel and touch the walls and curbs, with their fingers and feet, but also with their soul.

When a member of this group came to a cross roads, they took a moment to observe, be inspired, and to ruminate upon what they saw and felt inspired by. A mysterious thing would happen, and they would find their feet turning in one of two directions. What caused them to take a right by the Seine, and not a left? It may have been a piece of wood floating towards the bank, it may have been a cat which flit behind a lamppost. The wood, cat, lamppost, and the moon’s shadow were signs to read, like in a book or a map, and the SI members moved their body through the pages of a book they knew of as Paris, the book of their life.

We, too, can walk through our city, our life, and learn to read signs. In doing so, meaning and storylines will bear relevance to our own lives, offering something a bit more vital than news headlines and fragmented stories flickering through our Netflix night.

The title of Andrzej Jon Wrobleski’s exhibition is Unseen Forces of Nature in Art and Design, and each artwork on display reflects a moment in the artist’s reading of both art and life. His work in industrial design may surprise many art enthusiasts in the West, who see artistic beauty as free from function (art for art’s sake). I think there’s a place for this, if only to wrest art away from the prying hands of our times. There is something timeless about art, something which serves eternity, and infinity, and shouldn’t be limited by what kind of technological needs we have, or what kinds of social issues the politicians are saying we should care about today, or even what social needs community advocates are demanding art serve.

However, there are some creative souls who can do both. Wrobleski, for example, understands the multi-dimensionality of art. While creating an object that may be used for industry or travelling on business, he wants the object to not only fulfil its function, but to resonate with the other signs of our world in such as way as to allow us flights of fancy, or imagination. Good design responds to natural forces in ways which lift the parameters of our mind for just long enough to allow in new light and vision.

Systems of signs are like forests, with roots sunk low and labyrinthine, and tall canopies which soak up the nuance of light. Taking a walk through the world, in built as well as unbuilt environments, allows time to slow down, allowing us and encouraging us to observe, be inspired, ruminate, and to read our lives for meaning we may not otherwise divulge.

Speaking of reading, the Igneus bookstore offers decades of observation, inspiration, rumination, and ways of reading. Take a few moments to browse our library. Each title offers one free poem, so you can get a sense of how each poet uses the languages in an effort to reach out and change your life for the better.