buy the book: InVerse by Melinda A. Smith

buy the book: Entangled: a collaboration across time and space

Melinda scooped me up on Twitter, where I’d been responding to poetry tweets with poetry tweets. Since then we’ve recruited each other for several projects, flexing Melly’s mad video skills here at Igneus Press, and myself guest-posting on her blog. We challenge each other in the best ways.

Melinda Smith has a PhD in neuroscience, two kids, a husband, and a dog. She’s also branded herself Iambic Beats, a powerhouse of immersive electronic music and spoken word poetry. She’s collected science-based poems for an anthology, ENTANGLED, and found a publisher for one novella while she puts the wraps on another. Mel loves drawing other artists into her projects, but she’s a versatile painter herself.

I don’t know how she does it all, so I asked her.

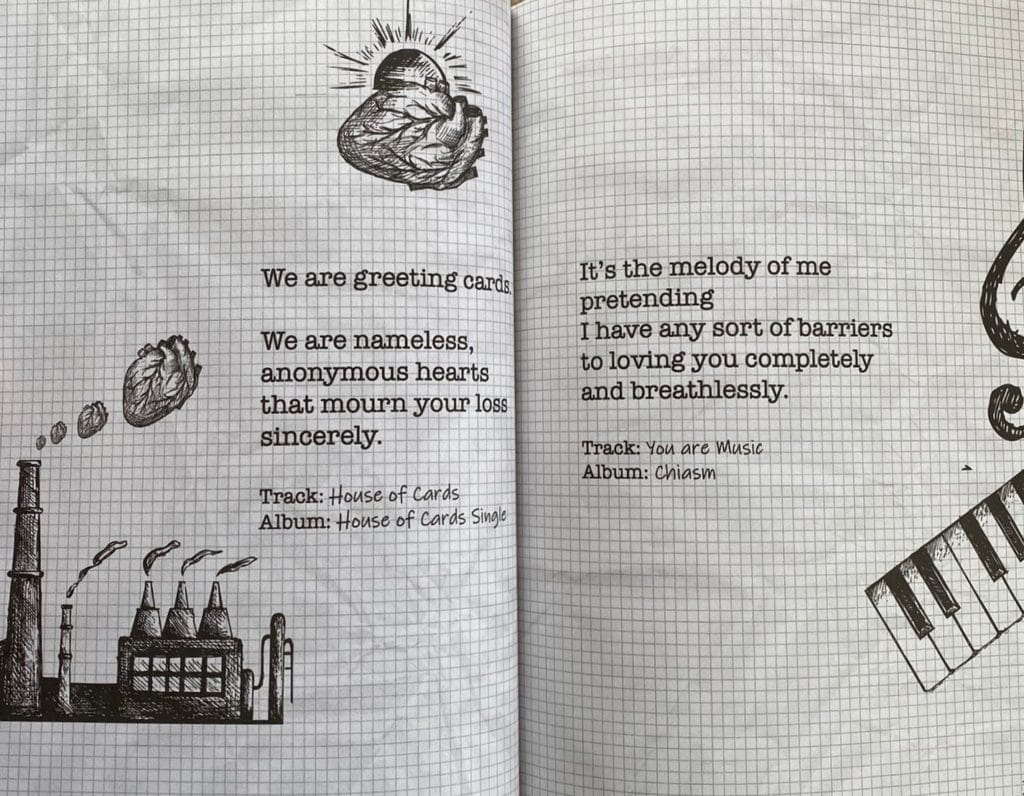

me: Your new book, InVERSE, is a compilation of lines from your spoken-word music albums. How did you decide you wanted to do this?

MS: I don’t necessarily consider myself the best poet. I am just at the beginning of the learning curve. Because I spent so many years as a scientist, I think I tend to tell more than show in both poetry and fiction, and this is something I’m really working on. But sometimes I have lines that really get at what it means to be human. I have certain lines that I’m proud of, that I think make a person stop and think. And I guess I just wanted to combine some of these lines in an approachable format, where it has a look and feel of going through an Iambic Beats notebook. I found this Ukrainian artist who does this wonderful line-sketch art and I think all together the effect works. Sometimes you don’t need a whole poem, but a few words to get your mind thinking, you know? I left space at the end of the book for people to write their own snippets of poetry. I’m hoping to see what everyone comes up with!

Music and poetry are not mutually exclusive. They are parts of the same body. The facts of this world, the truths, are bones and muscles. I say poetry and music give us the eyes and ears.

– melinda a. smith

me: How did the spoken-word album project begin?

MS: Here’s the thing. Music and poetry are not mutually exclusive. They are parts of the same body. The facts of this world, the truths, are bones and muscles. I say poetry and music give us the eyes and ears. A piece of music has verses or movements and a bridge where poetry has stanzas or sections and often a defined “turn.” I started to hear these elements as one when I read poetry that I loved. I started playing with electronic music and creating it around lines of poetry and the project took off. I use recordings of myself or others reading poetry and I combine them with original music.

But I am, by training, a scientist. I still find wonder in the science behind all the ethereal. So I often include scientific themes or even snippets of readings or lectures in my music so that the listener hears several aspects of any topic. For example, my forthcoming release NeurOnFire is all themed around the mind. Songs cover anything from memory or our perception of dreams and time to weightier subjects like empathy, depression, and self-harm. Scientific readings are layered in with poetry and music, along with real words from people around the world discussing what depression feels like to them. Overall, I believe my Iambic Beats project is meant to welcome all forms of expression and to show everyone that we are all part of the same race. We all have feelings; we all wonder about the universe; we all deserve a voice.

me: But you also sing & write music…?

MS: Yes! I do a lot of things and I’ve gotten good at them. I say this not to sound egotistical but because I think we ALL do a lot of things but have become constrained by far too few labels and boxes. If you’ll allow a brief (or maybe not) tangent… Labels are useful. They do important things. “I am a medical doctor” tells us that this person has the requisite training to care for certain physical needs. “I am ____’s mother” demonstrates legal and social authority to pick the child up from school, etc. But what happens when we define people by those labels? That doctor goes home at night and maybe paints or plays mah jongg. Maybe they are also a world class cellist. Don’t even get me started on how we label moms who are (gasp) whole people apart from their maternal roles. Taking this further into a more complicated territory: “I am autistic.” We know that medical/behavioral diagnoses can be validating and critical for obtaining any needed services/medications. But as we know, labels like this can be detrimental. This is why we are now supposed to say “a person with autism” rather than “an autistic person.” Now to my actual point.

I am not an artist, or a singer, or a writer, or a poet, or a mother, or a scientist. I am all of these things. I am a whole person. I have a white belt in karate (and yes I am proud of this because it shows I am at the beginning of something). I began learning digital art. I produce electronic music. I get labeled “mom” all the time. And I want to yell, “hey, I’m a person aside from making two kids.” But we all do this. Isn’t a writer also a reader by nature? Isn’t an artist also someone who takes in art? Isn’t a mother/father also a child? I believe we’ve been taught the lie of breadth versus depth: Be an expert at something. Don’t show people your failures. Be the most and the best. In reality our breadth strengthens our depths. I believe being a poet made me a better scientist and vice versa. “Bad” at art? Do more art and be “bad” at it. It will inform your writing. And besides, it will feel good to do.

me: Do you have any other poetry projects in the works?

MS: I write a lot of poetry, mostly short twitter pieces. I also write longer pieces to work through difficult emotions or life phases. I will likely publish something in the future, but I don’t yet know what that will look like.

As for Iambic Beats, look for my latest release July 25, 2022, NeurOnFire. Through the end of August, all proceeds of InVERSE and any of my other merch or music will go to The Jed Foundation, a non-profit org dedicated to mental health and suicide prevention in young adults.

Further Exploration:

Entangled: a collaboration across time and space is Melinda’s brain-baby, an anthology of science-based poetry by 10 poets from across the globe. Buy the book here at Igneus Press: Entangled.

Ellipsis Imprints is another fine Small Press hailing from Durham, England, established in 2020. Have a look at their titles here, including SUM by Melinda A. Smith. Read more about publishing with them here.

Bandcamp is the place to find aural and visual creations by Iambic Beats, aka Melinda A. Smith. InVERSE is available elsewhere on the internet, but if you buy it here on Bandcamp Friday, the website gives all proceeds to the artist. Through the end of August, Iambic Beats will donate all proceeds to The Jed Foundation, a non-profit org dedicated to mental health and suicide prevention in young adults.

Iambic Beats is the locus for Melinda’s spoken word/electronica production. Go get lost; you’ll be alright.

Hear more on Soundcloud, including MC Mel (born to Raise Hell) in one of my favorite tracks: Dream Dopamine on All Channels

All Things Melinda are here: https://www.sciencegeekmel.com/ where Melinda blogs about science, fiction, poetry, music, and her upcoming books. Feel the polymathy!

Iambic Beats covers feature art by Sionann Mastromonico, a talented artist based in Quebec, Canada.

The artwork of InVERSE was provided by Linework Stock, based in Ukraine.

Coming Into Balance is a blog created by an autistic mother to an autistic child.